Fixed Point¶

We practices translating some numbers using a fixed point representation with 8 bits, so there are 8 places

Places¶

Eights¶

Fours¶

Twos¶

Ones¶

Halves¶

Quarters¶

Eighths¶

Sixteenths¶

Example numbers in Fixed point¶

1.5¶

or:

12.75¶

1100.1100

or:

7.5625¶

0111.1001

or:

15.9375:¶

or:

Prelude¶

What do we mean by representation?

Computers are electrical devices, there are circuits that calculate everything, using gates that represent logical operations.

In order to get the data (the thigns we want to compute) through the ciruits we have to represent the values somehow.

We discussed previously how we could represent success/failure with 0/1.

You may have seen ASCII codes before: those are numbers to represent each character, that is how characters are represented in a computer.

Sometimes, we mix representations within a single bit string:

object instructions could use the first few bits to represent the operation and the rest to represent a value (so we can encode an instruction in a single register)

negative numbers (the first bit is sign and the rest represent places)

a toy object instruction¶

let say we have am CPU that can do 4 bit operations and has 4 control bits (that determine what operation it will do across the ALU + controls for A,D registers & PC)

then we might have an 8 bit register ROM.

the operation @3 might represented as 01000011 if @ is indicated by 0100 on the controler and then the last 4 bits 0011 represent the value 3

negative numbers¶

we use one bit to represent the sign. and then e have two choices for the rest of the bits:

representation | how to negate | how to read |

one’s complement | flip all the bits | note the sign, flip all the bits back |

two’s complement | flip the bits, add 1 | note the sign, flip all the bits, add one |

Try it out on integer exposed

For example, set it to 3 and then use the ~ button to flip the bits and add one by flipping the 0 in the ones place to a 1 (add one), that ends up at -3

so in 8 bit signed integer 3 is 00000011 and -3 is 11111101.

Try a few other cases in integer exposed

Two’s complement is themost common

Floating Point Notation¶

We can write numbers in many different forms. We have written integers through many different bases so far.

For example in scientific contexts, we often write numbers (in base 10) like:

We can use a similiar form to represent numbers in binary. Using base 2 instead of base 10.

Floating point numbers are not all exact¶

Let’s look at an example, we add .1 together 3 times, and we get the expected result.

We’ll use python here, but you can do this in any programming language.

.1+.1 +.10.30000000000000004However, if we check what it’s equal to, it does not equal .3

.1 + .1 + .1 == .3FalseThis is because the floating point representation is an approximation and there are multiple full numbers that are close to any given number that cannot be expressed exactly.

However, the display truncates since usually we want only a few significant digits.

Even rounding does not make it work.

round(.1,1) + round(.1,1) + round(.1,1) == round(.3,1)FalseInstead, we use subtraction and a tolerance:

(.1+.1+.1 - .3)< .0001TrueFloating point IEEE standard¶

Now, lets see how these numbers are actually represented.

IEEE Floating Point is what basically everyone uses, but it is technically a choice hardware manufacturers can make.

Initially in 1985

Reviesd in 2008 after 7 year process that expanded

revised in 2019 after 4 year process that mostly added clarifications

Next revision is projected to 2028.

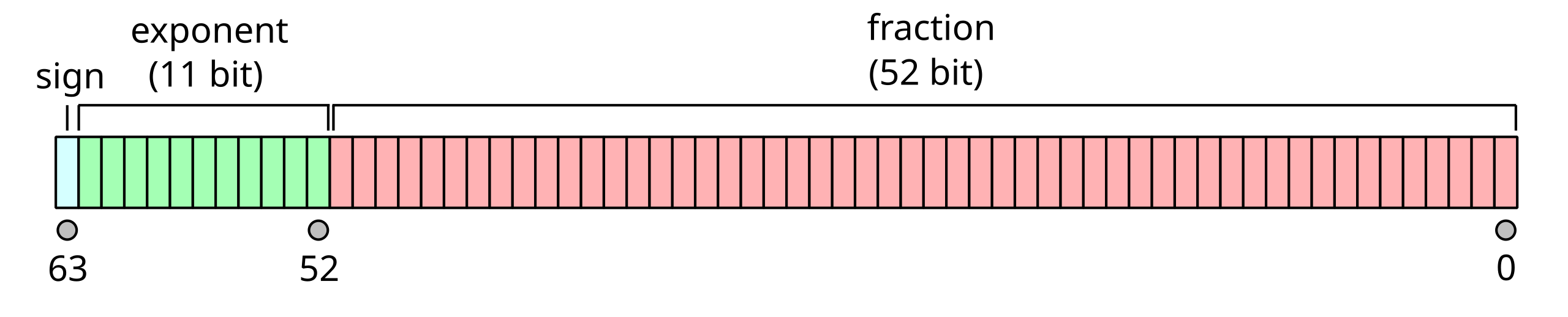

this is a double precision float or binary64 inthe current standard.

it was called double in the original, offically, so it is commonly called that still, even though it is no longer the formally correct name.

In this case we will 1 bit for sign, 11 for exponent and 52 for the fraction part

Figure 1:a visual representation of a 64 bit float:

How do we read a number like this?¶

if the sign bit is and the number represented by the exponent bits is and the 52 bits are number from right most is 0 and the last one is 52.

where:

is the sign bit is

is the number represented by the exponent bits is and

the 52 bits of the fraction are numbered from right to left (the rightmost is and the leftmost is ).

means we are working with fractions instead of integers in the sum.

means the sum for

So, for example:

0 01111111111 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000we have and and all of the .

we can follow the equation, and interpret the bits to get:

and for

0 01111111111 0100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000we have and and all of the , except . following the equation, we get:

Why use e-1023 for the exponent?¶

2**112048so 1023 is half -1, this means that we split the possible range of numbers that we can represent in the exponent to positive and negative, meaning the whole expression ranges from large(21025) to small(2-1023)

How do we get numbers into this form?¶

Now, let’s return to our example of .1.

First we take the sign of the number for the sign bit, but then to get the exponent and fraction, we have more work to do.

Let’s take the equation we had from the standard:

If we think about the fraction and how we add fractions, by reaching a common denominator. Since they’re all powers of two, we can use the last one.

and we can expand the sum to a different notation for visual clarity

And apply a common denominator:

So then this becomes a binary number with 53 bits (the 52 + 1) and a denominator of 252, let’s call that number so we have:.

we can then combine the powers of 2.

So in order to return to our .1 that we want to represent, we can represent it as a fraction and then approximated it in the form above.

means approximately equal to

after some manipulation:

Since we want to use exactly 53 bits to represent , we want to be greater than or equal to 252 and less than 253.

Since we can say

and we can also say that

(larger denominators is smaller numbers if the numerators are the same)

We can put any numerator that is the same across all :

and simplify the outer ones to only have a single exponent

If we combine Equation with our previous inequality from Equation, we can see that the best is 56, by taking either side or .

We can confirm this in a calculator

2**52 <=2**56/10 < 2**53TrueNow we can get the number we will use for , from Equation.

We want to get as close to .1 with our fraction as possible, so we get the quotient and remainder, the quotient will be the number we use, but we use the remainder to see if we round up or not

q,r = divmod(2**56, 10)Now, we check the remainder to decide if we should round up by 1 or not.

r6so we round up

J = q+1

J7205759403792794then we can check the length in bits of that number

bin(J)'0b11001100110011001100110011001100110011001100110011010'we could count above, or since there are 2 extra characters to tell us it is binary at the start we can take the len and subtract 2:

len(bin(J) )-253This is, as expected 53 bits!

The significand is actually 52 bits though, the representation just always has a 1 in it, see the 1 added before the sum of the bits in Equation or on float.exposed when the exponent is 1023 (the green bits; so that the multiplicative part of Equation is ) and the significand is 0(the blue bits)

significand = J-2**52

significand2702159776422298We have so to solve for we get

e = 52-56+1023

e1019Now lets’ confirm what we found with the actual representation:

First we can plug into float.exposed and see that is very clsoe to .1 and if we increase the significand at all it gets farther away.

Second, we can check in Python. Python doesn’t provide a binary reprsentation of floats, but it does provide a hex representation.

float.hex(.1)'0x1.999999999999ap-4'the

0xcan be dropped from readingafter the p is the exponent of . Which matches the approximation we found.

the rest we can compare to the value we found for J

hex(J)'0x1999999999999a'Third, we can test by computing the approximation:

(J)/2**56 ==.1TrueWe can also see how close the numbers one above and one below are:

(J-1)/2**56 - .1-1.3877787807814457e-17(J+1)/2**56 - .11.3877787807814457e-17these are the closest numbers we can represent to .1 meaning we, for example cannot represent

.1 - 1.2*10**-180.1.1 + 1.2*10**-180.1If we add these tiny values it does not change the value at all.

.1 - 1.2*10**-18 ==.1TrueThe same thing happens for very large numbers, 4503599627370496 is the beginning of a range in float64 where the closest numbers we can represent are 1 apart, so for example:

4503599627370496.0 +.54503599627370496.0doesn’t work; it cannot represent 4503599627370496.5

Above 9007199254740992 we cannot even represent odd integers, only even for a while and then it gets more and more sparse.

9007199254740992.0 +19007199254740992.0

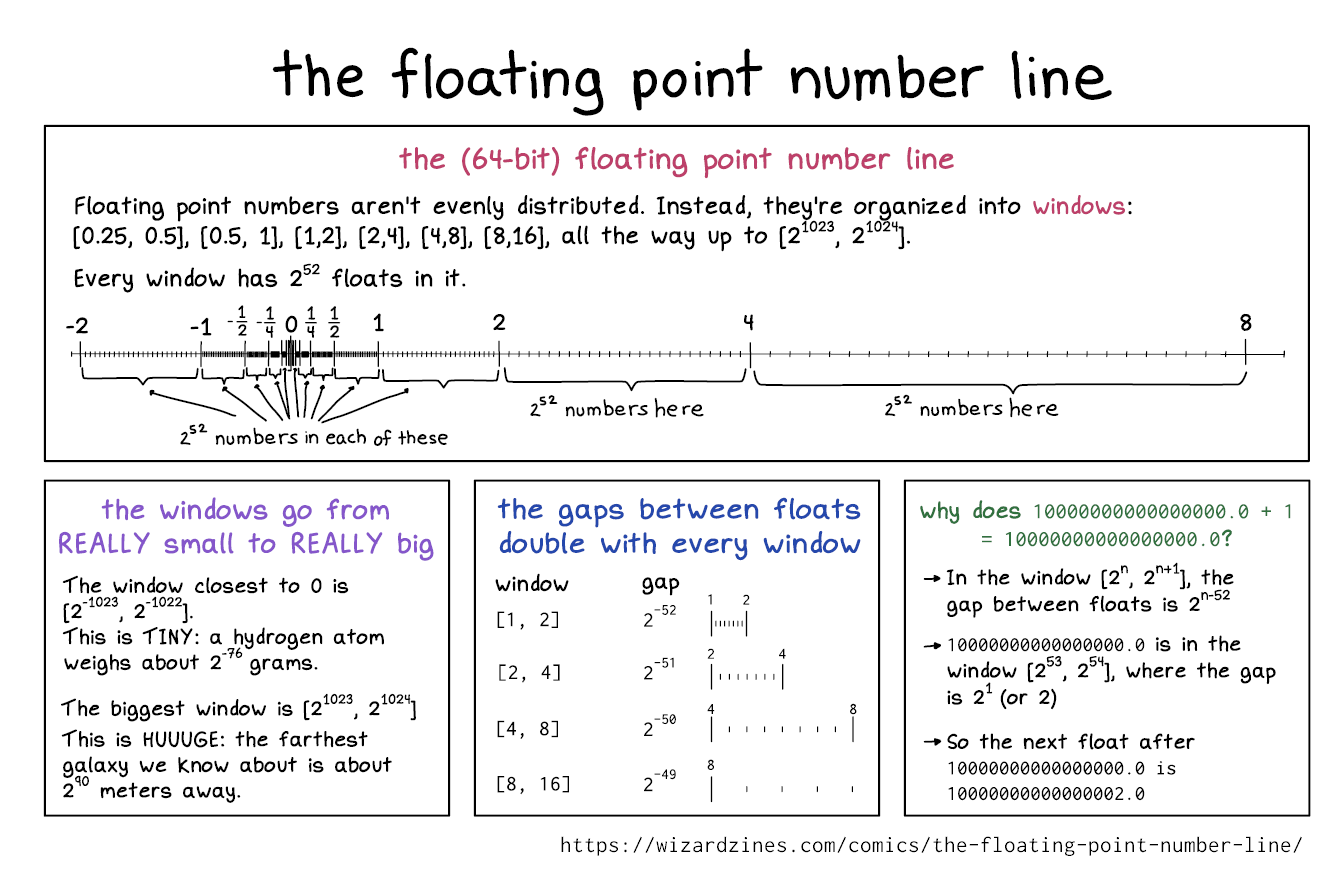

The floating point number line is not uniform. source

Prepare for Next Class¶

think about what you know about networking

make sure you have putty if using windows

get the big ideas of hpc, by reading this IBM intro page and some hypothetical people who would attend an HPC carpentry workshop. Make a list of key terms as an issue comment

Badges¶

Review the notes from today

Write a C program to compare values as doubles and as float (single precision/32bit) to see that the issue we saw with .1 is related to the IEEE standard and is not language specific. Make notes and comparison around its behavior and include the program in a code cell in cdouble.md

Review the notes from today

Write a C program to compare values as doubles and as float (single precision/32bit) to see that this comparison issue is related to the IEEE standard and is not language specific. Make notes and comparison around its behavior and include the program in a code cell in cdouble.md

In floatexpt.md design an experiment using the

fractions.Fractionclass in Python that helps illustrate why.1*3 == .3evaluates toFalsebut.1*4 ==.4evaluates toTrue. Your file must include both code and interpretation of the results.

Experience Report Evidence¶

Nothing separate

Questions After Today’s Class¶

How do calculators get exact decimals if the computer can not store all the exact values?¶

Calculators also have to approximate numbers if they are digital calculators.

this is a good explore topic

Is it possible for a number to accidently reach infinity?¶

In theory, yes, but in practice most programming languages handle this in some way, for example Python just does nothing:

1.79769313486231570814527423731704356798070567525844996598917476803157260780028538760589558632766878171540458953514382464234321326889464182768467546703537516986049910576551282076245490090389328944075868508455133942304583236903222948165808559332123348274797826204144723168738177180919299881250404026184124858368*10**308 + 11.7976931348623157e+308but if you try to increase this number any it goes to infinity

Do neural networks need larger floats?¶

Typically no, you can learn more about quantiation though.

Are there circumstances where using a different representation that is not floating point is necessary?¶

yes! we will see some in lab next week.